Reposted from Ted.com

Art so often seeks to capture the beauty of the natural world — from cave drawings of animals, to paintings of landscapes, to sculptures of the human form in marble, bronze or wood. But in this playlist, find artists and designers who take this to the next level, making art based on the laws of nature and the invisible workings of biology itself.

Tom Shannon: The painter and the pendulum

In this interview, John Hockenberry questions artist Tom Shannon about his metallic sculptures that levitate, and about how his scientific inspiration has evolved over time. Shannon says that his art starts with the need to solve a question — a process similar to scientific exploration. In the privacy of Shannon’s studio, we see work that challenges the idea that objects can’t defy gravity, as well as a sculpture that simply exemplifies the complex relationship between earth and sun.

Drew Berry: Animations of unseeable biology

Ever wondered what a molecule looks like? Well, your naked eye won’t help answer that question. “Molecules are smaller than the wavelength of light, so we have no way to directly observe them,†says biomedical animator Drew Berry, who was awarded a MacArthur Fellowship in 2010. By immersing himself in the world of cutting edge scientific research, Berry has made molecular and cellular biology accessible for the masses. In this talk from TEDxSydney, he uses intricately rendered animations to traverse the DNA highway into the depths of cells.

Doris Kim Sung: Metal that breathes

Before houses had air conditioning, they used tiny windows and thick walls to combat extreme weather and regulate temperature. Before cars had air conditioning, they overheated and thus signaled to us the overuse of energy. Fast forward to today, where impossibly cold stores have become the norm. How do we make our buildings work better? At TEDxUSC, biology student turned architect Doris Kim Sung shares how she studied the human body to learn how skin regulates body temperature and, from that research, developed the smart material known as “thermo-bimetals.†She reveals how panels of this material can be used to create responsive ‘building skins’ that help our buildings breathe beautifully and efficiently.

Margaret Wertheim: The beautiful math of coral

In 2005, Margaret Wertheim and her sister, Christine, asked the internet and art institutions alike to join an interdisciplinary project that combined math, marine biology, environmental activism and feminine handicraft. With thousands helping, they set out to crochet the largest coral reef in the world to raise awareness of the impact global warming has on this massive, living ecosystem. In this talk from TED2009, Wertheim explains that the mathematical study of hyperbolic structures (aka, things frilly and curly) discovered in the 19th century couldn’t be depicted until Dr. Daina Taimina began to knit in 1997 and eventually crocheted a coral reef.

JoAnn Kuchera-Morin: Stunning data visualization in the allosphere

If you can imagine being inside a computer that looks like an omnitheater, you can partially imagine the mysterious, three-story metal arena known as the Allosphere. This echo-free chamber, connected to a very large computer, was created as an interdisciplinary center for artists, scientists and engineers to work together.

Lucy McRae: How technology can transform the human body

Lucy McRae is a self-proclaimed ‘body architect.’ How does one get that title? She has a background in ballet, architecture and fashion, with an added interest in transforming the human body. While working for Philips Electronics, McRae worked on projects that resembled sci-fi realities, but working on prototypes wasn’t enough. She began to ask questions about communication and sexual attraction —  like “Would it be possible to create swallowable pills that allow you to perspire perfume to attract partners?†Watch this talk from TED2012 to see her provocative, visionary work exploring the limitless future of biology and technology.

According to the US State Department, 79% of all cocaine transported from South American to the United States travels through the small Central American nation of Honduras. One tragic result of this drug trafficking is that the country’s second largest city, San Pedro de Sula, has eclipsed Juarez, Mexico as the Murder Capitol of the world with more than 1200 murders last year in this city of approximately 800,000 people. This evening’s PBS Newshour includes a short documentary on the city (a full version will air next month on the BBC). This documentary gave me pause to consider the ecological and environmental justice impacts of drug use, drug trafficking, and the war on drugs. Not only does the ecological footprint of international drug trafficking continue to grow but also at issue are the unregulated growing and manufacturing processes, the toll on infrastructure and energy used to grow and combat the drug trade, the toll on the forests, urban environments and other places and materials involved, and of course, the human ecological issues involved in drug use and in the bodies literally left to bleed in the streets in cities like San Pedro de Sulas and lives torn apart by violence and addiction. This short news documentary did not explicitly frame this issue in terms of ecological justice but left me feeling fully aware of the importance of ecomedia studies for understanding such issues in their full complexity, both in terms of the ecological images on display for viewers but also in the human/environment ecosystem of the drug trade and war on drugs.

The recently published Spring 2013 issue of ISLE includes two new essays adding to the field of ecocinema studies.

In “Regarding Things in Nashville and The Exterminating Angel: Another Path for Eco-Film Criticism” Adam O’Brien integrates the work of materialist scholars like Jane Bennett with classical film scholars like Sigfried Kracauer to imagine a new offer materialist film criticism. Here’s a short excerpt:

“What I intend to argue here is not only that there exist significant correlations between the ideas of Jane Bennett and early film theorists such as Kracauer, but also that ecocritical film studies may benefit from building upon those links, more specifically by according ‘things’ a greater degree of importance in interpretations and analyses of film fiction. This development would manifest itself in two, different but closely related ways: attention to the ways in which things in film can resist allegorical or symbolic extrapolation, and in the interpretation of dramatic action as materially driven” (260).

In “Patrick Keiller’s Ambient Narratives: Screen Ecologies of the Built Environment” Jon Hegglund builds on the work of Scott MacDonald to explore both the visual and acoustic aspects of Keiller’s feature-length films London (1994), Robinson in Space (1997), The Dilapidated Dwelling (2000), and Robinson in Ruins (2010). Here’s a short excerpt:

“Keiller’s stylized use of ambient sound accords well with MacDonald’s call for a ‘retrained perception’ of eco-cinema. But the ambient sound of the film must still co-exist on the soundtrack with the film’s [Robinson in Space] only narrative element: the voiceover narration. This narrative dimension, as attenuated and uneventful as it is, still includes enough material to activate the viewer’s narrative drive. Because we are cued to read the film as a narrative, however, weak those narrative elements are, we empathize with its characters and try to project some sort of narrative development and resolution. In the case of Keiller’s film, and other ambient narratives, the hyperformalism of the visual dimension and the attenuated flatness of the characters directs us toward an interpretation of the relationship between characters and space” (290-291).

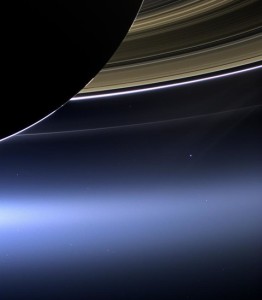

In case you have not seen it yet, here is the incredible photo of our little blue planet as taken by NASA’s Cassini–Huygens spacecraft, which is currently orbiting Saturn.

Asian Eco-cinema & media: Human, Animals, Environment and Beyondâ€, SCMS 2014 (March 19-23, Seattle)

With a growing awareness of global environmental issues, and an attempt to address the growing interest in films and media in relation to various ecocritical theories, this panel invites papers that fall within the study of media and films in Asia in relation to ecological and environmental issues. It seeks to expand the field of ecocinema/ecomedia studies towards a broader coverage in Asian contexts.

From the fictional depictions of Asian environmental crises (e.g. The Impossible, Bhopal: A Prayer for Rain), documentaries of environments shaped by urban developments and post-disaster reconstructions (e.g. Still Life, 3.11 Surviving Japan), artistic representations of human, nature and wilderness (The Mourning Forest, Uncle Bonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives), to social media coverage of pollution problems in Asian cities, ecological and environmental issues in Asia have increasingly been exposed to the outside world through fictional films, documentaries and various forms of media.

Possible themes may include, but not limited to:

– Specific environmental issues in Asia

– Concepts of Nature, cities and the environment in Asia

– Defining ecomedia/ ecocinema/ eco-film criticism

– Asian eco-philosophical thoughts in films (e.g. Buddhism, Confucianism, Daoism, Shintoism, etc.)

– Eco-materialism/ New Materialisms in film/media

– Green movements and social media in Asia

– Animal studies, animality, ecojustice

– Waste, toxicity, refuse and pollutions

– Climatic changes, natural disasters in film

– Limitations of media and film in ecocriticism/ green studies

– Other related topics

The Society of Media and Cinema Studies (SCMS) 2014 Conference will take place March 19-23 at the Sheraton Seattle Hotel. You are invited to submit a 300 word abstract, a brief bio, or any question to Kiu-wai Chu at kiuwaichu@gmail.com.

Deadline for proposal submission is

August 4, 2013. For further information about the conference please refer to the following link:

http://www.cmstudies.org/?page=call_for_submissions

Kiu-wai Chu

Comparative Literature, University of Hong Kong,

| Kiu-wai Chu Department of Comparative Literature, University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong Email: kiuwaichu@gmail.com |

Seaworld’s Unusual Retort to a Critical Documentary.

You can find the trailer to Blackfish at their website.

Related, Michigan State University’s Animal Legal and Historical Center has a short blurb on laws regarding captive orcas in the news. And as has been making the rounds on FB and the eco-sites, recently India is the fourth country to ban captive dolphins and orcas.

Check out the new section on our resources page: Syllabi and other Ecopedagogical Goodies. If you have taught a class, helped organize a degree program, or if your university has offered a symposium or is developing other resources or if you know of other people/places doing pedagogical work involving the intersection of media and environment please contact srust.at.uoregon.edu or smonani.at.gettysburg.edu and we will be sure to add your resource to our growing archive of ecopedagogical goodies.

While the description below focuses on human rights, correspondence with the editors indicates a strong interest in festivals that also engage non-human rights.  I.e., they are interested in scholars considering film festivals that explore environmental issues pertain to both human and non-human rights.

Time frames:

Abstract of 500 words must be received by Monday 30th September, 2013

A short bio and publications to be included

Acceptance/ non-acceptance will be sent out by Monday 14th October, 2013

Proposal to publisher immediately after

Chapters of 5 500 – 6 000 words to be received by Friday 28th February, 2014

Description

If we take as departure the idea that film festivals are knowledge-sites *

and* communal spaces that call forth a specific type of spectator, then we

can begin to ask questions about the particular spaces and spectators

created by activist/ human rights film festivals. As these sorts of

festivals negotiate a variety of discourses, most particularly film

festival and the social/ human rights issue that organises them

thematically, one of the most central discursive features is that which

centres on ?social change?. Through this idea[l] the spectator is called

forth as an active participant, the films are to act as motivators, and

discussions that usually follow film screenings are to expand on the issues

raised by the film and motivate further. In this way gazing at others?

troubles is expected to be more than a passive watching of trauma, but

involve an ethically and politically engaged spectator who will traverse

the world of the screen and that of material being through social action.

Although much has already been written about the mediating and distancing

effects of witnessing ?distant suffering?, in this volume we wish to

interrogate this idea as one that has productive elements but also quite

distinctly politico-cultural dimensions that, in the space of activist/

human rights film festivals, configures its viewing publics in quite

definite ways. (see attached for fuller description)

Contributors can consider the following topics as possibilities, but others

can be proposed:

– theoretical engagement with humanitarian spectatorship as it applies to

human rights/ activist film festivals

– human rights/ activist film festivals as discursive sites

– Critical engagement with the idea of ‘social change’ and what this means

for the spectator in a human rights/ activist film festival

– How does ‘the political’ enter into the construction of an active

spectator as filtered through human rights discourse?

– What are the political dimensions to be considered in the creation of the

human rights spectator that are different to other forms of activism? e.g.

the global/ internationalising dimension

– in what ways is human rights discourse being recreated differently in

different national contexts subverted, or modified?

– If film festival discourse relies on elements of cinephilia, how is this

present/ absent in human rights/ activist film festivals?

– Film festivals were originally established to subvert the dominance of

Hollywood and promote national cinemas, while human rights demand an

internationalising gaze; how do these apparently opposing imperatives

converge in a human rights film festival to encourage the spectator to

create social change?

– How is ‘the film act’ apparent in activist/ human rights film

festivals?

Abstracts/ bio to be sent to:

Dr. Sonia Tascon

*sonia.tascon@monash.edu*

Dr. Tyson Wils

tyson.s.wils@gmail.com